SDA Book Club: “Crafting Aotearoa” by D Wood

February 19, 2021

This month we have a bonus entry into the SDA Book Club with Crafting Aotearoa: A Cultural History of Making in New Zealand and the Wider Moana Oceania, edited by Karl Chitham, Kolokesa Māhina-Tuai, and Damian Skinner, and reviewed by D Wood.

Crafting Aotearoa: A Cultural History of Making in New Zealand and the Wider Moana Oceania

My credentials for this review: I am a New Zealand citizen and lived there on and off for 15 years. Since I was formerly married to a Pākehā (non-Māori New Zealander), mixing in professional, academic and family circles, I have insider knowledge of the society and culture. My doctorate from the University of Otago (Dunedin, NZ), focusing on the modern craft movement, was commended for its contribution to New Zealand art and design history. Except for three footnote references to my thesis, my scholarship is not included in Crafting Aotearoa.

Mary Hannah Tyer Artificial flowers 1885, Wellington. Courtesy of Te Papa.

Skinner, Māhina-Tuai and Chitham have given themselves a broad mandate for the words ‘Aotearoa’ and ‘craft’. Aotearoa is Māori for New Zealand. Citizens have petitioned for a bilingual name, Aotearoa New Zealand, but legally the country is still New Zealand. Ethnically the population is 70.2 percent European, 16.5 percent Māori, 15.1 percent Asian and 8.1 percent from the Pacific Islands (via Stats New Zealand). The latter group consists of people who identify as being from Samoa, the Cook Islands, Tonga, Fiji and so on, herein described as Moana Oceania (Pacific Ocean) because this phrase “empowers and privileges Indigenous perspectives” (16). The book travels to Norfolk Island, Guam, the Solomon Islands, Rarotonga, etc., to capture stories about material culture. Despite a significant Asian population, some of whose Chinese ancestors arrived during the gold rush in the South Island in 1860, the emphasis in Crafting Aotearoa is on Pākehā, Māori and Moana Oceania making.

Maker unknown Tīvaevae ta’ōrei (patch work quilt) circa 1900, Cook Islands. Courtesy of Te Papa.

Moving to ‘craft’, the editors state: ‘To fully embrace the richness of handmaking in Aotearoa, terms like ‘art’ or ‘craft’ and the typical objects that they can accommodate need to be shaken up—and perhaps even replaced entirely’ (12). This shaking up has resulted in contributions about film and photography, performing arts, iconic New Zealand manufacturing like Crown Lynn Pottery, housing, graphic design and punk culture. In the Preface, for example, the Blunt umbrella, manufactured in China, is justified for inclusion because it was designed by a New Zealand engineer, has New Zealand decorative motifs and is made “at a single factory dedicated to achieving high standards” (14). Blunt Umbrellas are bespoke—made for a particular user—not in the sense of handmade but as luxury goods. The editors suggest that craft and the handmade are becoming fluid notions, a concept that offers a panacea to the elimination of craft education in New Zealand at primary, secondary and tertiary levels. This absence, beginning in the late 1980s, is not part of Crafting Aotearoa.

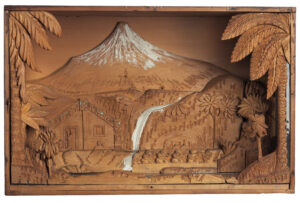

William Gee Carving scene circa 1905, Wellington. Courtesy of Te Papa.

Having pointed out that Crafting Aotearoa is not about Aotearoa and not about craft, it is definitely A Cultural History of Making in New Zealand and the Wider Moana. As such it is a hybrid of fact, opinion, anecdote and marvellous images. It is a coffee table book in the sense that it can be picked up and browsed. Most pages have three parts: the editors’ text in black serif font; the invited authors’ essays in small red sans-serif font; and translations of Māori and Moana words running across the bottom, a helpful addition since foreign words are repeated. The editors’ text, whose author is not identified, ranges through contemporary and historical in single chapter. For instance, Section 3: ‘Craft and Belief’, begins with clothing and adornment for attending a Tongan Methodist Church on White Sunday, the first Sunday in May, 2019, and moves on to the London Missionary Society (LMS) that sent missionaries to Tahiti, Tonga and the Marquesas in 1797. The discussion between that landfall and the Church Missionary Society’s arrival in New Zealand in 1823 includes contents of an LMS Museum Catalogue, colonial furniture, the education of Māori students in Australia, cross-cultural sharing of craft skills like patchwork, crochet in Tuvalu, Benjamin Woolfield Mountford’s 1860s gothic Canterbury Provincial Buildings (destroyed in the Christchurch earthquake of 2011), and the expropriation of ‘idols’ from Rurutu (French Polynesia) by the LMS. The chapter concludes with Māori carving in Christian churches in New Zealand.

Susan Holmes Jacket and skirt ensemble circa 1975, block printed silk, Auckland. Courtesy of Te Papa.

My research, concentrating on Pākehā craft, because I am not qualified to delve into Māori beliefs and practices, revealed the separation of craft according to race. The Crafts Council of New Zealand (1977-1992) did not embrace traditional Māori crafts (e.g. weaving of plant fibers, carving of wood and stone, tattooing) and when Māori taonga (treasured items) appeared in Te Māori at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (1984) they were deemed art not craft. Crafting Aotearoa addresses the separation and dichotomy. The latter chapters ‘Craft and the Modern’ and ‘Craft in the Contemporary’ show the hybridity of making in New Zealand, with artists bridging aesthetics, materials and genres. This is not a recent phenomenon—Anton Seuffert immigrated to New Zealand from Bohemia in 1859 to make exquisite furniture decorated with marquetry that combined his European and Moana sensibilities (he’s not mentioned here although his work is in Britain’s prestigious Royal Collection Trust).

Despite its errors and omissions, anyone unfamiliar with or enchanted by the South Pacific will enjoy Crafting Aotearoa. It pays tribute to the presence of handmaking in the region and is further global evidence of the recognition of craft as a vital part of society.

Moka Poi Pulou (hat) 1990s, New Zealand. Courtesy of Te Papa.

–D Wood earned a Diploma in Crafts and Design in furniture at Sheridan College, Canada, and an MFA in Furniture Design at the Rhode Island School of Design (2000). Her PhD addressed the history and presence of studio furniture in New Zealand in the context of the contemporary craft movement. D has given presentations at international conferences and published extensively in respected journals. A book of essays, Craft is Political, which she edited and contributed to, will be published in 2021 by Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

- Publisher: Te Papa Press (buy it here)

- Date: November 2019

- ISBN: 9780994136275

If you’ve read this book, leave a comment and let us know what you think!

Do you have a recommendation for a recent fiber-related book you think should be included in SDA’s Book Club? Email SDA’s Managing Editor, Lauren Sinner, to let her know!

Related Blog Articles

aotearoa

Member Spotlight: Jeanette Verster

aotearoa

Artist Spotlight: Imogen Zino

aotearoa

Artist Spotlight: Georgina Young