In the Studio: Elizabeth Fram

March 17, 2021

Every day I look forward to getting up and heading into the studio. Rain or shine, happy or sad, it’s a place of discovery, of bringing ideas to life, and of finding resilience when things don’t turn out as planned. My excitement is grounded in a love of process and its accompanying assurance that even techniques that have been repeated many times over, present unexpected revelations that propel the work forward in exhilarating ways.

Elizabeth Fram, studio.

I tend to examine ideas and narratives based in simple observations that often go unnoticed, yet which merit deeper consideration. My pieces expand on the idea of the unsung beauty of the quotidian while exploring other facets of the notion of “hidden in plain sight”, including camouflage and unrecognized identity.

Elizabeth Fram Caught Red-Handed (detail) 2019, stitched-resist dye, silk, embroidered, 18” x 24”. Photo: Paul Rogers.

Every piece revolves around layering dense fields of stitched marks with colorful patterns created via shibori dyeing. My materials are straightforward: raw silk, thread, and dye. Despite their simplicity, the wide scope of visual and tactile possibilities that are achievable with these basic materials highlights that limitation is a fertile growing medium.

Elizabeth Fram Espresso & Peanut Butter 2018, stitched-resist dye, silk, embroidered, 14” x 11”. Photo: Paul Rogers.

Adding a sink to my studio ten years ago was a benchmark that changed the direction of my work dramatically. Once it was installed, I learned basic shibori techniques through an online course with Glennis Dolce of Shibori Girl Studios. The game-changer of that experience was being introduced to Colorhue dyes. Ever mindful of my environmental impact, I shy away from fiber-reactive dyes because of the copious amounts of wasted, dye-saturated water. The overarching advantage of Colorhue is that it bonds instantly and molecularly to protein fibers (I use silk), requiring a fraction of the water, and resulting in very little pigmented waste.

Elizabeth Fram, studio dye set-up.

My degree in Art from Middlebury College, in tandem with post-college jobs in graphic design and free-lance illustration, balanced by watercolor and pastel painting, have all contributed to building a broad foundation that continues to influence my work. Yet, drawing is a cornerstone that has become as integral to my practice as stitching. I try to draw daily as a means toward a more frequent and regular sense of completion, an advantage that my heavily hand-stitched pieces don’t allow. Because of this, after many years of working abstractly, figurative imagery is now central to my pieces. Working back-and-forth between stitching and drawing underscores the reciprocity and influence each discipline has upon the other, impacting my overall approach toward composition, form and mark-making.

Elizabeth Fram Quiet Moment 2017, stitched-resist dye, silk, embroidered, 11” x 14”. Photo: Paul Rogers.

Looking for a new subject to sketch every day has led to paying closer attention to my surroundings and recognizing the extraordinary in the ordinary. Inspiration lies everywhere. It is in the simple curve of an object meeting its shadow as it cuts across a surface, or in the layers of color and pattern found within my garden beds or the woods surrounding our house. I’ve long admired Japanese gardens as masterful examples of composition and texture. And I am pulled to work that shows evidence of process and materials, allowing one to trace the path of the artist’s hand.

Elizabeth Fram Cultivating An Oasis (in-process) 2020, wrapped-resist dye, silk, embroidered, 27” x 15” x 16”. Photo by the artist.

A residency at the Vermont Studio Center opened the door to a deeper exploration of various stitched-resist patterns and techniques. Back in my home studio, my goal was to further incorporate dyed patterns with stitched imagery. Ultimately, I developed a process where the two are intimately intertwined. The work is accomplished in three stages. Embroidering an image with white silk thread on undyed raw silk, I follow the surface planes of the subject with lines of thread, much the same as with a pen or pencil. That white-on-white work is then hand-dyed with a stitched-resist technique, resulting in a pattern that envelopes both the embroidered image and the silk it is sewn upon. The image is then coaxed back out into the open by re-embroidering with another layer of threads in contrasting colors. I am planning to use this technique to develop a body of work that will center on women whose contributions to society have remained largely unrecognized.

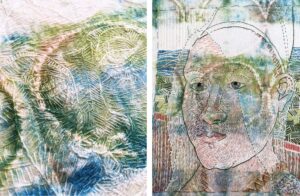

Elizabeth Fram in-process works. Left: white-on-white embroidery, silk thread, raw silk; Right: inspiration drawing, graphite, paper, 12” x 9”. Photos by the artist.

Elizabeth Fram in-process works. Left: first layer of embroidery after shibori dyed, silk; Right: second layer of embroidery bringing the image out from the dyed pattern. Photos by the artist.

Meanwhile, with the arrival of Covid-19, my work has taken a bit of a left turn. Using shibori and embroidery techniques to explore the impact of the pandemic, I have been making a series of 3D houses that reflect on our collective sheltering-in-place experiences, channeling the range of emotions that have been prevalent this past year. Many of the pieces include branches and stalks foraged from our woods and garden, representing the literal and figurative support nature has offered so many of us during this challenging time.

Elizabeth Fram Until The Bitterness Passes 2020, stitched-resist dye, stitched, knotted, silk, foraged branches, 16.5” x 7.5” x 8”. Photo: Paul Rogers.

As I’m sure is true for many, my studio has become a refuge in the wake of 2020. I write regularly about my process and discoveries in my bi-weekly blog, Eye of the Needle, an exchange of ideas and resources.

elizabethfram.com | @elizabeth_fram

Elizabeth Fram When We Emerge 2021, stitched-resist dye, embroidered, silk, buttons, foraged branches, 21” x 12” x 10”. Photo: Paul Rogers.