How Hooked Rugs Moved Me from Silence to Voice by Catherine Heilferty

June 16, 2023

I’m a pediatric oncology nurse, a nurse educator-researcher, and a hooked rug artisan who has been surrounded by artistic women all my life who never considered themselves artistic. Of the hundreds of traditional rug hookers I have met over the years, only a handful consider themselves artists. Thanks to them, I’m making that distinction now as a 60 year-old who started an MFA program in fall 2022.

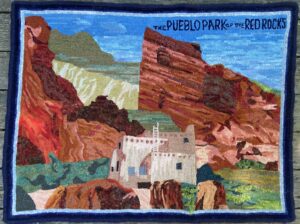

Catherine McGeehin Heilferty, Red Rocks Postcard, 2022. Linen, hand-dyed and recycled wool, 3.5 x 4 feet. Photo by the artist.

I taught myself the basics of the craft about 20 years ago after a visit to the Elizabeth LeFort Museum (now the Hooked Rug and Homelife Museum) on the Cabot Trail in Cheticamp, Nova Scotia. I appreciated the simplicity of the technique and the endless potential for complexity in design. When I returned home, I found friendship and support in the guild community of expert makers and teachers. Within that community, guided by the tradition of consistent technique, uniform materials, insular exhibitions of work, I found comfort and felt nurtured as a fledgling artist. I took classes, hooked my own designs, and hand-dyed wool to suit the projects. With the support of other artists, I had progressed from novice to exhibitor, creating over 60 pieces over the years.

Catherine McGeehin Heilferty, Red-breasted Sunfish, 2006. Linen, hand-dyed and recycled wool, 4 x 3 feet. Photo by the artist.

In the early days, made pieces with more focus on craft than art. For me, craft is about honing skills until stitches, loops and finished pieces that can be replicated with consistent high quality. I set out more recently to create artworks that begin with concepts and relationships; works that integrate broader artistic notions and practices. The best path for me was to become a student again—to spend time with educators skilled in art practices, guiding and mentoring, and with students who shared similar goals, even if not similar life experiences. I took inspiration from Old in Art School by Nell Irvin Painter, and over a year later, I moved from I can’t do it to why can’t I do it? It was the unexpected welcoming nature of the MFA program director and others that made the difference. I ignored the art school legends about suffering through cruel or dismissive mentorship and critique.I came to the MFA program to create abstract works of varying form and style. I wanted to play with color using fiber the same way Joseph Albers did with paint.

Catherine McGeehin Heilferty, Deerfield Society, 2020. Linen, new and recycled wool, 2 x 3 feet. Photo by the artist.

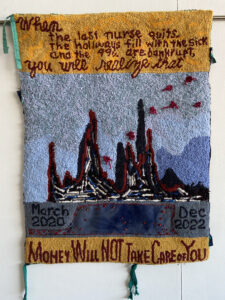

Meanwhile, in my teaching life I felt a tectonic shift in undergraduate nursing students and my colleagues. Others noticed it too. The vibe said, “Covid-19 is over. Resume life as if it never happened.” Even though classes had been on campus for a year already, the caution and compassion evident in that first year back in person completely vaporized. Faculty raised the bar on expectations to pre-pandemic levels in what is already one of the most rigorous majors. Student reports of anxiety and attention problems remain high even as life returned “back to normal,” whatever that means now. Students described work conditions they saw during their clinical experiences that made them question why they were becoming nurses. Healthcare systems, perfectly structured to exploit nurses’ work, returned to pre-Covid-19 staffing. The cavernous nurse shortages returned to the routine shortage we lived with for decades. The sounds of clanging pots and pans echoing through Manhattan in gratitude for front line workers ended. I guess this is what the new normal is now. The same emotional and physical labor as before Covid-19 but with less help and added PTSD.

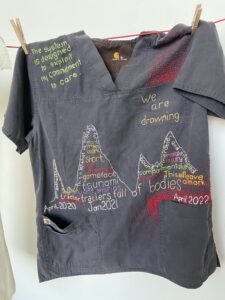

Catherine McGeehin Heilferty, Wash Day, 2023. Cotton nurse uniforms, cotton thread and blood stains, 6 x 4 feet. Photo by the artist.

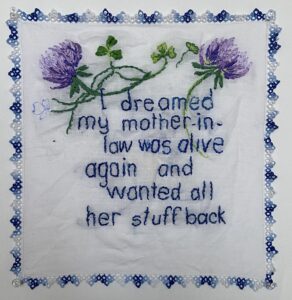

In art classes, the readings gave me license to question this new reality. Why am I doing this? What is art for, anyway? I found inspiration in protest posters from the environmental movement of the 1970s. Works on subversive stitching and activism sparked little fires. The three main firestarters were: The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine by Rozsika Parker, Crafting Dissent: Handicraft as Protest from the American Revolution to the Pussyhats, edited by Hinda Mandell, and Fray by Julia Bryan-Wilson. In these, I found support I didn’t know existed for the frustration I was feeling. I began to express this frustration in the pieces I made. For the first time, I felt able to move from the silence and invisibility that traditionally inhabits feminism, hooked art, and nursing to voice my concerns about US healthcare and to advocate for vulnerable students who are rising into nursing education.

Catherine McGeehin Heilferty, #GetMePPE, 2023. Cotton and polyester scrub top, cotton thread, 3 x 4 feet. Photo by the artist.

The risks have been much fewer than I expected when I took the leap into the MFA program. Last year, the list of reasons for why I shouldn’t begin was long. I’m 60, I took only a few recreational art classes over the tears, no BFA, and I have a full-time job teaching nursing. My creative life was centered in the niche craftsperson community of traditional rug hooking. I will be seen. That was the biggest risk: I will be seen.

Catherine McGeehin Heilferty, Manmade Natural Disaster II: US COVID deaths per week, 2023. Linen, recycled wool, recycled scrubs, scrub ties and cotton thread, 3 x 4 feet. Photo by the artist.

This is what happened when I took that dive. In our group of MFA students, just a couple are over 30. I listened to these young people talk about their art and felt at home and on another planet all at once. They are bright, dedicated, and hilarious. They take their work seriously, but not themselves. They ask me questions that are challenging and important for me to answer. And even though I am working on a subject foreign to most of their life experiences, they accept its importance and cheer me on. They appreciate the message in my work. The thing I feared the most became the best part: I am seen.

–Catherine McGeehin Heilferty is a fiber artist, pediatric oncology nurse and nurse educator, and the youngest of seven. Her traditional hooked rugs include themes of nature, travel, loss, and healthcare work. She explores the intersection of historically feminine and silenced experiences within needlework and nursing.

Catherine McGeehin Heilferty, Oh, Marilyn, 2023. Embroidered cotton handkerchief with cotton thread, 9 x 9 inches. Photo by the artist.