Creative Process: Linda Colsh, Strong Characters & the Baggage of QUILT

December 2, 2010

(The following interview with Linda Colsh was conducted via email in June 2010 by SDJ Editor Patricia Malarcher. Her profile of Colsh–recently published in Quilts: Continuity & Change (Fall 2010) issue of the Surface Design Journal–is a distillation of the complete text, which appears below.–Ed.)

Patricia Malarcher: Your work shows a sophisticated knowledge of many disciplines including painting, printmaking and computer graphics. What does the quilt format add to those other practices?

Linda Colsh: What I most like about making art quilts is the creation of the content and imagery, which could be accomplished in other media. However, I like the puzzle-solving and math of patchwork as well as the properties of cloth –—how it feels (quilts are tactile; fabric is soft and supple) and how it looks (how it absorbs and reflects light). Work that can be rolled or folded alleviates practical and cost problems of exhibiting, particularly shipping and storage. The actual quilting I do is minimal and purely functional, holding the layers together and giving a small amount of surface relief.

PM: Your work has a warm, humanistic quality—it’s surprising to learn that you manipulate your images with a computer. Can you describe your process?

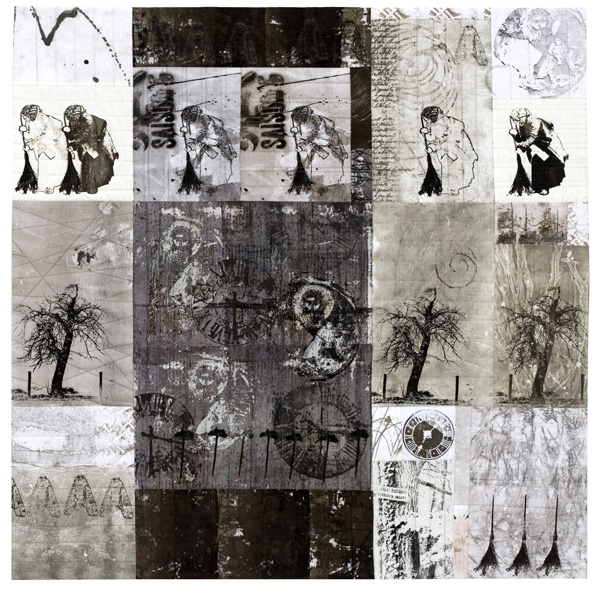

LC: It’s a multi-step, multi-level process of capturing. First, a person captures my attention, and I capture their image in digital photos. I strip away the context—literally, by stripping away the photo’s background and figuratively by selecting individuals I know nothing about other than what their appearance says to me. I develop a character with a story, adding visual elements for setting and whatever props convey type and message.

LC: It’s a multi-step, multi-level process of capturing. First, a person captures my attention, and I capture their image in digital photos. I strip away the context—literally, by stripping away the photo’s background and figuratively by selecting individuals I know nothing about other than what their appearance says to me. I develop a character with a story, adding visual elements for setting and whatever props convey type and message.

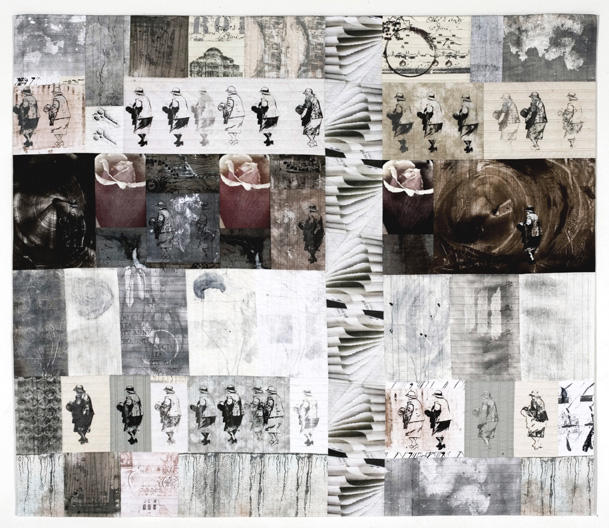

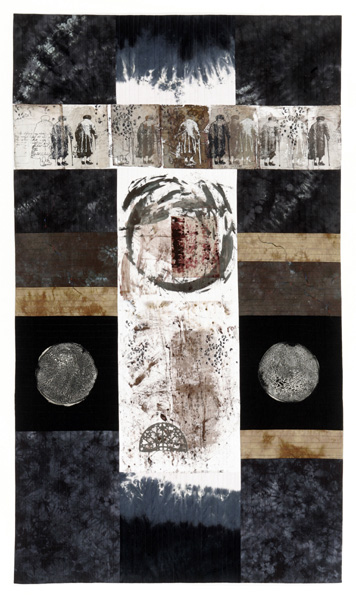

I upload my photos and alter them in Photoshop. After removing the background and cropping, I desaturate to remove color and resize. The fun begins with the magic of Photoshop. Minimally, a character will have a positive, negative, and line image, each made into a screen. In addition to the computer work that prepares images for screenprinting, I do direct digital printing on fabric.

There is always parallel work in my notebooks where I develop personality, narrative, and get to know my people. The humanism is from the thinking, writing, and drawing by hand.

PM: You achieve visual depth by using repetition without duplication. That is, you often repeat a figure, but change it—e.g., from a tonal to a linear interpretation. Are you intending more than simple visual interest?

PM: You achieve visual depth by using repetition without duplication. That is, you often repeat a figure, but change it—e.g., from a tonal to a linear interpretation. Are you intending more than simple visual interest?

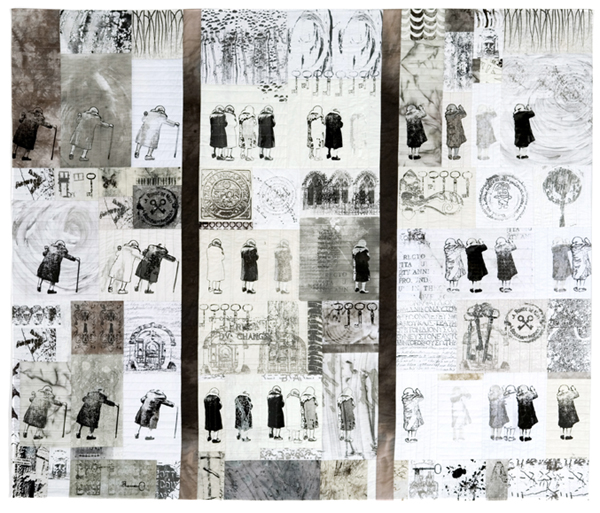

LC: Until recently, each figure was developed from a single photo, but every reiteration of the image is ever so slightly different. The change is accomplished by varying the screen(s) used—how they are layered, slight color or value changes, allowing the registration be a little off. Recent work has included several poses to indicate passage of time—the character moves to accomplish an event.

Aside from the obvious visual interest in such variety, repetition emphasizes the essential character; small changes reinforce the individuality. Showing various aspects of an image acts as a metaphor for rounding out and exposing a person’s character, much as the device of theme and variation in music, especially jazz, sets up excursions from or alternative treatments of the basic theme while retaining its essential character.

Once the viewer notices that each figure is a little different, the eye is held and the thought process is initiated. People whose images I’ve captured are, for the most part, ignored by everyone around them. I’m saying, “Okay, you’ve ignored these people in the street, now think about them.”

PM: What is the source of the text incorporated into your quilts?

PM: What is the source of the text incorporated into your quilts?

LC: The text (often just fragments) comes mainly from two sources: (1) from antiquarian shops and book or brocante markets, I collect old papers (postcards, letters, books—even torn and damaged ones). (2) I photograph notes, inscriptions, or single words on signs, gravestones, drain covers—anything where the lettering catches my fancy or the wording is unusual or interesting. Your work conveys a sense of time’s weight on the person, but it strikes me as a meditative reflection on life as much as social critique. Does that match your intentions?

I see in the people I portray a valuable resource, often untapped and too often completely unnoticed. The body of knowledge and immense experience collected over a long life is a treasure. We are used to computers and, lately, the cloud being our storehouses of data; the older population–the majority unconnected digitally–is a vast and fascinating storehouse of information that is in peril of being lost.

I also am a quiet activist for the elderly, I hope. I put images of people with wrinkles, gray hair, bald heads, stooping shoulders, on the internet and in exhibitions. I intentionally make art of what and who I consider beautiful in a far more interesting way than what is sold as ideal beauty by purveyors and hawkers of fashion.

PM: You have two degrees in art history. What was your particular area of interest?

LC: My declared major and minor were Early Italian Renaissance and Classical Greek and Roman Art. When I entered grad school for my Masters, I wanted to major in Northern Renaissance Art, but that professor was on sabbatical so I specialized south of the Alps. I kept current in another area by working as a grad assistant for Modern Art. It’s one of those circles closed that, years later, I’m here in the midst of Flemish art, a few minutes’ train ride from the Musée Magritte.

PM: Has your knowledge of art history influenced your artwork?

LC: I can see and analyze composition—a huge help when designing. Iconography was a reason I chose to pursue the art historical periods I did. Symbols are challenges; figuring out what makes them iconic and what they mean. So it was no great leap that my own artwork makes frequent use of iconic imagery and my notes and drawings explore images from many angles to pack as much meaning into each as possible.

The list of artists who inspire me is long and changing all the time. I collect icons when traveling. Does the iconic figurative imagery influence my work or is my collecting icons a symptom of my desire to work figuratively? It must all tie together.

PM: Has being an American living in foreign countries given you a particular perspective on life?

PM: Has being an American living in foreign countries given you a particular perspective on life?

LC: There’s a kind of apartness existing in us who live in an “in between” culture; we are “other” to the natives, but are also “other” to our own culture because we are somewhere else. Along with adventure goes a desire to record, somehow, and report all the different-ness.

Even though I now feel distant from my first overseas experience—two years in Seoul, Korea in the late 1980s—I recognize how important difference is to one’s perspective. Life as “the stranger” is a big jolt (imagine being the only “round eye” in a subway car), but being surrounded by a strange environment is exciting and enhances powers of observation. A floor-sitting culture made chairs significant. Papers with anti-American messages were dropped from balloons into our garden, just 30 miles from the DMZ. I saw trees with shamanist rags hung as prayers and, after a while, could sense Confucianism’s permeation of attitudes toward many things, including the elderly.

PM: Can you say more about the impact of travel on your life?

LC: My art and my husband’s job [with NATO] have facilitated countless chances to go places I probably would not have experienced otherwise. Each morning when I open up the Trib and read with greater understanding and empathy about places like Sarajevo or Thailand, I realize how broad and rich my life is. I’ve trembled with excitement in front of the artwork I studied in college: Hagia Sophia, Charlemagne’s Palace Chapel, van Eyck’s Mystic Lamb altarpiece, Durham Cathedral. By accidents of timing and chance, I have been to the Olympics and was in Tiananmen Square during the student demonstrations. The fall of the Berlin Wall and eastern countries opening to travel have led to both my icon collection and a lot of travel that influences my imagery.

PM: Your characters have been developed from photographs you’ve taken in many different countries. Yet there is a common quality about them. Would you comment on that?

LC: I’m quite aware that the image of an older person, alone, will draw people in. The initial attraction may be the presumed vulnerability. But my characters are strong as well. I’m interested in finding and emphasizing the worth of a life lived. I deliberately choose those who don’t conform to youth and packaged, wrinkle-free beauty. Because I find experience, and long, sometimes hard-won, knowledge to be treasures that too many ignore, my intention is to put those values in front of the public.

I’m attracted to loners, but do have an interesting “couple” or two on the computer drawing board. Some find my subject matter lonely and depressing, but I find the opposite. The individuals who attract my attention are silently but purposefully making their way in an environment that is not easy and where they are ignored and invisible. I like quiet strength, determination and independence.

PM: You were a writer and editor early in life. Have you considered doing a book on the stories of your characters?

PM: You were a writer and editor early in life. Have you considered doing a book on the stories of your characters?

LC: I would LOVE to do that—it would be a rounding out of what I’ve been doing. My hope is that a book can be a goal when we move back to the US in a few years.

PM: At this point, what are your concerns about your career and the field in general?

LC: Finding studio time is a concern; there never seems to be enough. On the other hand, I look at being on the road as research time when I mine a lot of imagery.

Like many others, I’m concerned about the baggage of “quilt.” I think of myself as an artist—no adjectives, no modifiers. If asked to be more specific, I would identify myself as a surface designer, fiber artist, or printmaker. I think the majority of serious studio quilt artists are surface designers and it’s a bit of a mystery why surface design isn’t more widely accepted as a nomenclature for the métier and medium.

PM: Apart from the images its streets have provided for you, how has being in Europe influenced your career?

LC: In my view, it is a positive to be distanced somewhat from the mainstream. The isolation of being an ex-pat on top of the working artist’s isolation provides a creative and introspective solitude that enables an artist to explore and develop in her own way at her own pace.

In Europe there are fewer opportunities for solo gallery shows and the fiber art audience, particularly serious collectors, is smaller. But there are unique opportunities here, like showing work in a medieval castle, Baroque church, or fortified farm—it’s a very special feeling to see my work in a venue older than my native country. I particularly value the special friendships and connections with artists from a wide variety of cultures.

For additional information, visit lindacolsh.com

2 Comments

Carolyn Bedford says

January 7, 2011 at 2:17 pm

Great article. Love the descrip of how to combine the mediums. Enjoy the sketches and taking quilts to new level.

donna joslyn says

January 13, 2011 at 12:09 pm

I like this too. I also focus on mixed digitized imagery - usually on textile, some on paper. I don't seem to fit the quilt category anymore, since most of the time the 3 layers and stitching seem to take away from rather than add to what I do. Do I call it surface design, mixed media, printing - just not really sure anymore. But maybe that's a good spot to be in as an artist.

Related Blog Articles

Creative Process

“Fringe: On the Edge of Fiber” — Out Now!

Creative Process

Friday Fibers Roundup: Craft & Color

Creative Process

“Standing Tall: A Heart-FELT Reflection” by Martien van Zuilen