False Cloth: Rejecting the Dichotomy of Front and Back by Kira Keck

February 23, 2024

I have a naturally tight craft hand, but this neatness is betrayed with one glance at the back of one of my pieces. I begin my embroideries with as little planning as possible—inviting colors to build and shapes to form as I stitch—leaving long floats in my wake. These floats look like brushstrokes, deliberate marks that seem to endear them to people who love Abstract Expressionism. For many years I resented this fetishization of what I considered an unintended consequence of my work. Recently, I have embraced this messiness—working on both sides of the cloth, leaving loose threads visible, and blurring the distinction between the front and back of a piece. This is a strategy I have also seen in the work of other queer fiber artists, such as LJ Robert’s stitched portraits and Aubrey Longley-Cook’s embroidered animations. I relate the use of both the front and back of an embroidery in a finished piece to the recto/verso in fiber discourse, as well as concepts of inversion in sexology and queer theory.

Kira Keck, Invert, 2021. Cotton cloth woven on a digital jacquard loom with embroidered penelope canvas, 25.5 x 6 inches.Photo: Katie McGowan.

More often applied to double-sided printing in books, the terms recto and verso can be used to describe the front and the back of a textile respectively. In many historic needlework traditions, the sameness of the recto and verso mark the pinnacle of skilled craftsmanship and are most highly valued, referred to as “true” embroidery. Putting a moral judgment to craftsmanship assigns openness, honesty, and integrity to works where the hidden back is identical to the front, which is often called the “right” or “correct” side. To invert something is to put something in a position opposite to its conventional order or arrangement. The concept of inversion was a prevalent theory of homosexuality in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. With an assumed binary of biological sex and gender, sexologists posited that same-sex attraction was an inborn reversal of gender traits (1).

Kira Keck, Mesh, 2021. Digitally printed cotton, liquid starch, embroidered penelope canvas, 65 x 41 inches. Photo: Katie McGowan.

Kira Keck, Mesh (detail), 2021. Digitally printed cotton, liquid starch, embroidered penelope canvas, 65 x 41 inches. Photo: Katie McGowan.

I connect the orderly front and messy back with my experience of neurodivergence and mental illness. The messy side is a part of myself that is meant to be suppressed, hidden. I must mask symptoms of depression and anxiety or the incessant quirks of an ADHD brain, presenting a neat and orderly front that is more acceptable to society. Order and disorder are a dichotomy I see within myself and my art. My sexuality and gender identity eschew heteronormativity and a gender binary. On both counts I am not in the correct orientation as many words we use to identify sexuality are based on a gender binary. I am transgender and non-binary, often describing myself as a queer dyke. This incorrect or unexpected orientation carries into my work as I constantly flip and rotate my embroidery canvas.

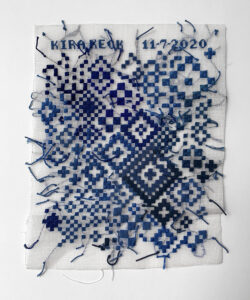

Kira Keck, Redline/RedWork, 2018. Embroidered aida cloth, 14.35 x 14.25 inches. Photo: Dan Meyers.

Kira Keck, Redline/RedWork (detail), 2018. Embroidered aida cloth, 14.35 x 14.25 inches. Photo: Dan Meyers.

Although I think more loose, expressionistic, or messy styles of embroidery are popular in contemporary practices, and aligned with general trends toward sloppy craft, most artists still treat the wrong/recto side as a “B side” or bonus content. Presenting the recto and verso sides of a piece emphasizes a physical flip—a refusal to choose a right or correct side. Textiles that are pictorial or hung on a wall are often thought of as two-dimensional or flat, but cloth is a pliable plane that exists in three dimensions. By treating all sides of a work as a complicated whole, questioning traditional conceptions of self, and collapsing hierarchies, I have cultivated a queer strategy in embroidery.

(1) Jonathan Ned Katz, Gay/Lesbian Almanac: A New Documentary: In Which Is Contained… (New York: Harper & Row, 1983).

kirakeck.com | @erotic_macrame

Kira Keck, Stability and Transparency, 2021. Embroidered interlock mesh, 8.5 x 11 inches. Photo by the artist.