Janet Echelman: The Complete Interview

June 27, 2013

Janet Echelman builds living, breathing sculpture environments that respond to the forces of nature—wind, water, and light—and become inviting focal points for civic life. Named Architectural Digest’s 2012 Innovator for “changing the very essence of urban spaces,” Echelman combines ancient craft with cutting-edge technology to create permanent sculpture on the scale of buildings.

Janet Echelman builds living, breathing sculpture environments that respond to the forces of nature—wind, water, and light—and become inviting focal points for civic life. Named Architectural Digest’s 2012 Innovator for “changing the very essence of urban spaces,” Echelman combines ancient craft with cutting-edge technology to create permanent sculpture on the scale of buildings.

In a recent e-interview with Surface Design Journal editor Marci Rae McDade, Echelman discussed how state-of-the-art research, tools and materials have expanded the scope of her creative vision worldwide.

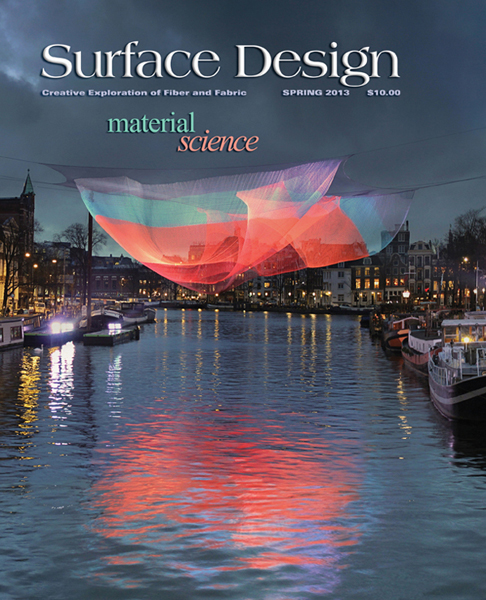

The unabridged version of that interview that follows is an SDA NewsBlog companion piece to the shorter printed article featured in Spring 2013 Material Science issue (shown at right).

MRM: The fluidity of air currents has been key component of your work since you began creating netted sculptures on the coast of India in 1996. As the Earth experiences more pronounced effects of global warming, how have weather patterns and scientific research influenced your work?

JE: I’ve been working on a series for 3 years called 1.26. It started in 2010, when I got a call from the City of Denver, host of the Biennial of the Americas, asking if I could represent the 35 nations of the Western Hemisphere and their interconnectedness in a sculpture.

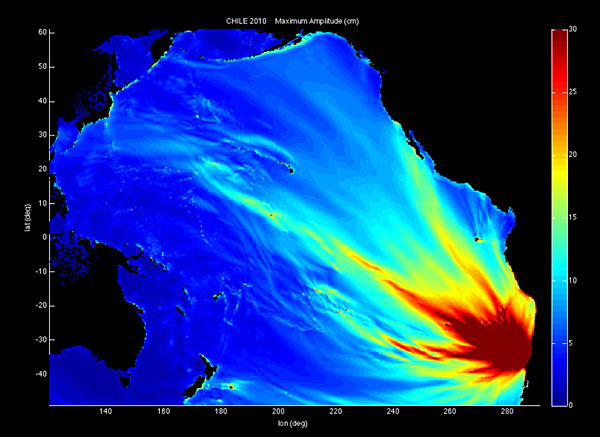

Of course I had no idea how to do that, but I said yes. I had been following the tragic earthquake that had just occurred in Chile, and I came across an article by a National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) scientist that measured the effects of the earthquake on the entire planet. I was surprised to learn the earthquake shortened the length of the day by speeding up the earth’s rotation by 1.26 micro-seconds. It was hard to fathom how a physical event in one part of the world could affect the flow of time—something I thought to be certain and inescapable, like the old saying about death and taxes. This became the catalyst for the artwork.

I then looked at the tsunami wave-height data gathered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). With their data set, my studio created a 3-dimensional model of the tsunami’s amplitude rippling across the ocean, which inspired my textile form. The result was my sculpture 1.26, referring to the microseconds by which the day was shortened when the earthquake redistributed the earth’s mass.

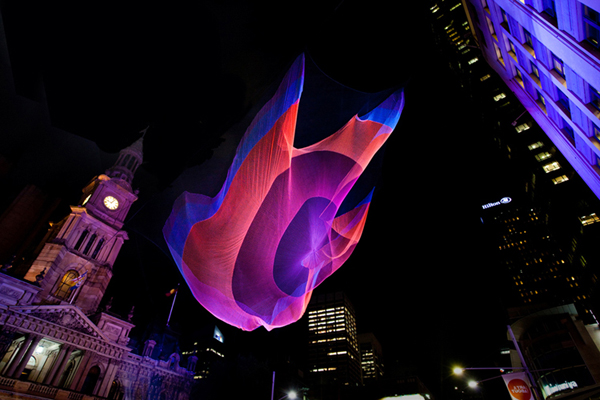

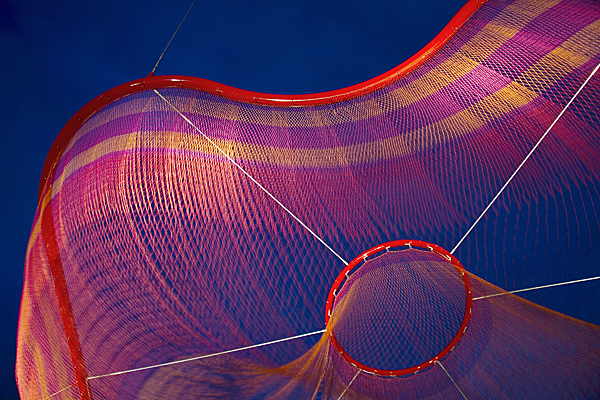

1.26 became a traveling piece that has debuted on 3 continents. After North America, it traveled to Australia in 2011, suspended from Sydney Town Hall over its busiest street, and to Europe in 2012-2013, suspended from the Amsterdam City Hall and Opera House over the reflective surface of the river. Because 1.26 is made entirely of soft materials, it is very lightweight and can attach to existing architecture without extra reinforcement. Its soft surfaces are animated by the wind, and its fluidly moving form contrasts with the rigid surfaces of the surrounding urban architecture. At night, colored lighting transforms the work into a floating, luminous form while darkness conceals the support cables.

MRM: Over the course of 15 years, you have crafted a new genre of public art that redefines urban spaces and energizes surrounding communities. Why do you think your work has had such a profound and uplifting effect on so many in different parts of the world?

JE: It’s not for me to say what kind of effect the work has, though I’m moved by the responses that people share. I hope my art creates an invitation to listen to our inner selves, and to connect us to one another in a public space. In that way, I hope my art can be a transformative element. In our busy urban lives, I feel a need to find moments of contemplation, and I hope my art can offer that to each person in their own way.

For San Francisco International Airport, I was asked to create a “Zone of Recomposure” for travelers after they go through security. I find calm in nature, and since airports seems to be completely devoid of nature, I wanted to bring it in.

For San Francisco International Airport, I was asked to create a “Zone of Recomposure” for travelers after they go through security. I find calm in nature, and since airports seems to be completely devoid of nature, I wanted to bring it in.

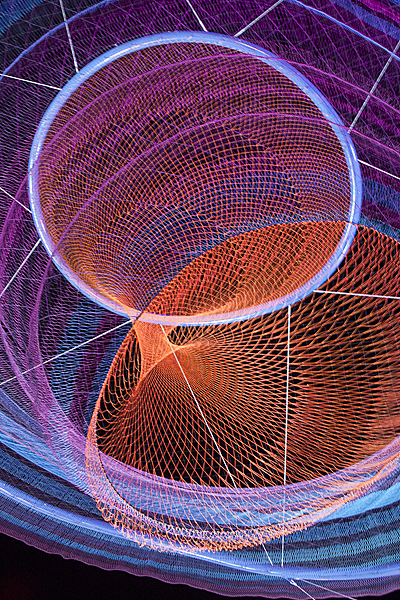

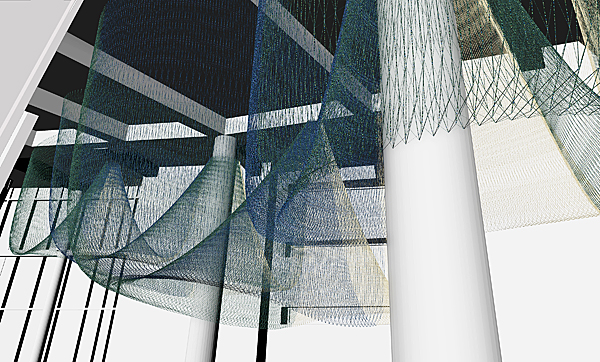

We did this with the installation Every Beating Second by cutting 3 round skylights into the ceiling and suspending delicate layers of translucent colored netting to create 3 volumetric forms.

During the day, sun streams through the skylights to cast real shadows that interplay with fictional shadows we embedded in the floor. At night, a program of shifting colored lighting makes the sculpture glow as computer-mechanized airflow animates the sculpture to suggest wind and the presence of nature within Terminal 2. Visually, the sculpture evokes the contours and colors of cloud formations over San Francisco Bay and hints at the silhouette of the Golden Gate Bridge.

I’ve been getting feedback that the sculpture is working, in terms of getting people to stop and look up – and slow down for a moment and contemplate phenomena. And I hear that total strangers have started conversations about the work.

MRM: The research and development phase for each of your projects has become increasingly complex over the years with the architectural and engineering challenges unique to each location. How has state-of-the-art 3-D modeling and other software provided solutions?

JE: We’re in the midst of a collaboration with the design software company Autodesk, who have been developing a tool that enables us to design textile nets and exert the forces of gravity and wind on them.

It’s so exciting for me as an artist to be able to draw out textile forms and very quickly understand how they will drape. The word “computer-aided” design has been around for about 30 years, but it seems that it used to be just about computers aiding documentation after designing was done. With this new tool, the computer is giving me feedback in real time that informs my design decisions. It’s pretty great.

MRM: Traditional textile materials could never survive prolonged exposure to the outdoor elements of rain, sun, heat, and cold. How have new high-tech materials and fabrication techniques helped solve these problems for you?

MRM: Traditional textile materials could never survive prolonged exposure to the outdoor elements of rain, sun, heat, and cold. How have new high-tech materials and fabrication techniques helped solve these problems for you?

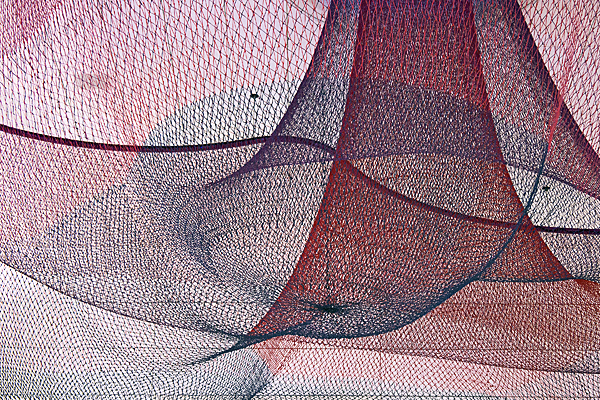

JE: When I began making my netted sculptures, they were fabricated completely by hand, made possible by my work with a group of fishermen in India whom I met during my Fulbright grant (example shown at left). All of my recent works are a combination of machine and hand-work. My studio uses hand-work to create unusual, irregular shapes and joints, and to make lace patterns within the sculpture. We utilize machines for making rectangular and trapezoidal panels with stronger, machine-tightened knots that can withstand intense winds, and the heavy weight of snow and ice storms.

After researching the location and drafting the design, I work with engineers and architects in our studio to transform my simple sketches into scale 3-D forms within a larger 3-D site model. The scale relationship of my work to the human body and to the architectural context is something I think about all the time. These models help me to adjust the scale of my artwork until it evokes the feeling I seek.

For Water Sky Garden at Richmond Olympic Oval, which premiered at the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics, I collaborated with engineers to prepare for the possibility of severe wind and ice storms. We calculated the size of the openings to allow snow to fall through. Every 20 years or so there is a serious ice storm there, and we wanted to plan for that without having to over-engineer the sculpture for something that rarely happens. So we designed a system that when the weight of ice sticking to the surface goes beyond a specific level, the steel ring attaching to the armature is designed to release the net, which can then be easily re-attached after the storm. This allowed me to keep the artwork with the lightness and elegance I sought, rather than over-building it.

Wind load is a primary concern. My outdoor nets are engineered to withstand hurricane force winds of 90 mph using proprietary aeronautical computer software written specifically for my work. Once we’ve ensured the integrity of the structure, we work with professional fabricators to turn my idea into a physical reality. I have great respect for the craftsmanship of our industrial workers.

The sculptures require us to use many types of high-tech fibers as well. We use different fibers for different parts of the sculpture, just as a spider uses many different types of silk for the various parts of its web.

For example, we use Honeywell Spectra®, a fiber more than 15 times stronger than steel (pound for pound), when we want to make large structural spans while retaining delicate diameter rope sizes. And when we need 100% UV resistance, we use WL Gore. TENARA® architectural fiber, which is made of PTFE (poly-tetra-fluoro-ethylene), the substance most widely known as the non-stick cooking surface Teflon®. Its exceptional colorfastness and resistance to high temperatures, chemical reactions, and stress allows the sculpture to withstand sun and wind over time.

For example, we use Honeywell Spectra®, a fiber more than 15 times stronger than steel (pound for pound), when we want to make large structural spans while retaining delicate diameter rope sizes. And when we need 100% UV resistance, we use WL Gore. TENARA® architectural fiber, which is made of PTFE (poly-tetra-fluoro-ethylene), the substance most widely known as the non-stick cooking surface Teflon®. Its exceptional colorfastness and resistance to high temperatures, chemical reactions, and stress allows the sculpture to withstand sun and wind over time.

We use a variety of different fiber types in each sculpture, depending on the function of the component and the harshness of the climate.

MRM: To realize each project, you constantly interface with architects, engineers, urban planners, designers, and scientists. How has working collaboratively with people from other disciplines created opportunities to learn new things and see the world from different perspectives?

JE: I sometimes have to pinch myself to make sure I’m not dreaming when I get to work with brilliant engineers, lighting designers, computer scientists, and architects. It expands the language with which I can speak as an artist. I am always learning from them – and it creates something greater than the sum of its parts.

MRM: Your 2011 TED talk has been viewed online by nearly a million people. Do you have any advice for other artists as they strive to effectively communicate their creative vision?

JE: When I started making art, my biggest challenge was learning to hear my inner voice and finding a way to notice and pay attention to my own ideas.

JE: When I started making art, my biggest challenge was learning to hear my inner voice and finding a way to notice and pay attention to my own ideas.

I began writing and drawing with my non-dominant hand, which gave me access to my more fledgling, vulnerable ideas that were being overpowered by my more conscious, skilled hand. Once I began to pay attention to these new ideas, the biggest hurdle was to learn how to respect them – and the way to respect an idea is to invest the attention and work needed to develop it. This was difficult, but learning to do so was an important step in my growth as an artist.

When developing an idea, I remind myself not to start with compromise. I envision my ideal goal—what would result if I had no limits in resources, materials, or permission. I’ve learned that eliminating options too soon is costly because many ideas might be more viable than they initially appear. They just need a chance to mature and develop.

In early design phases, I try to disregard both inner and external critics, imagining my goal as a reality, and then working backwards to figure out all the steps I need to take to make it so. I use inspiration and look towards people who accomplished unimaginable ambitions to achieve bold change in the world.

In early design phases, I try to disregard both inner and external critics, imagining my goal as a reality, and then working backwards to figure out all the steps I need to take to make it so. I use inspiration and look towards people who accomplished unimaginable ambitions to achieve bold change in the world.

If you start with yourself and make sure that you fully believe that what you’re doing will create positive change in the world, then you can go out and share your vision with genuine belief.

Being authentic is the most important thing when communicating about one’s art.

MRM: Your monumental sculptures change dramatically from day to night with the addition of spectacular lighting. What inspires your color choices and the choreography of each program?

JE: Different color palettes allow me to express a desired mood and content for my sculptures as related to the context and location. For Her Secret is Patience, my 145-ft-tall aerial sculpture in Phoenix, Arizona, I was inspired by the region’s distinctive monsoon cloud formations and the shadows they cast, in addition to forms found in desert flora and the local fossil record.

I created a lighting program in which the nighttime illumination changes color gradually through all four seasons. I selected the color temperatures to provide a sense of relief to residents of this extreme climate, shifting to cool hues in summer and warm tones in the winter. The lighting design also varies from night to night what portion of the sculpture is most illuminated, leaving some parts obscured in mystery, much like the phases of the moon.

For 1.26 Amsterdam, I collaborated with Philips Lighting Chief Design Officer Rogier van der Heide to experiment with using color opposite to neutralize the physical color of the twine to create an alternate mood. We call this scene the “launderette,” because we’re washing out the apparent color. We were thrilled with the dream-like, ephemeral quality this gave the sculpture, and its reflections in the undulating water below.

MRM: Do you have any new projects on the horizon for the coming year?

JE: I am working on several new commissions.

Right now, I’m in the middle of fabrication of an exciting sculpture for the Matthew Knight Arena at the University of Oregon. The work will highlight the role of spectators and the interconnection of members of the basketball team. It is a 30-foot-long form composed of 5 interconnected smaller forms that can only be seen in its entirety within your mind, because it turns the corner within the architecture.

The lighting is very special: it creates a new kind of silhouette shadow drawing on the wall.

Construction has begun for my artwork Pulse, for Dilworth Plaza in Philadelphia, a large urban plaza in the center of one of America’s historic cities.

I’m excited about how this work reshapes urban experience and uses a new material for me—water.

The artwork traces above ground the pathways of the 3 subway lines that run beneath the plaza’s new 11,600-square foot fountain, revealing the urban circulatory system, sort of like an X-ray of the city. The movement is designed to occur in real time, using a data feed of train arrival and departure to initiate the movement of 5-foot-tall curtains of “dry mist” composed of atomized water particles, illuminated by layered colored light.

MRM: More than any other artist practicing today, the sky is truly the limit for your awe-inspiring creative practice. Where would you like to see your work in the future?

JE: My dream is to transform hard-edged cities with soft, organic forms—to create spaces which foster calm and contemplation. I need to do it at the scale the city requires. I am asking myself How can I create this kind of change with something like sculpture? This is what pushes me to create.

My focus right now is to share my studio’s work with cities around the world, so more people can have a chance to form a relationship with the sculpture, watching its interaction with wind and sunlight as it changes through the years. To this end, I’m using my new lightweight structural strategies to create a new kind of artwork that can easily attach to the top of existing skyscrapers, traverse urban airspace and safely go above roads and public plazas.

My focus right now is to share my studio’s work with cities around the world, so more people can have a chance to form a relationship with the sculpture, watching its interaction with wind and sunlight as it changes through the years. To this end, I’m using my new lightweight structural strategies to create a new kind of artwork that can easily attach to the top of existing skyscrapers, traverse urban airspace and safely go above roads and public plazas.

I do this because I want to engage in people’s regular life – in ordinary places in cities that make up the texture of our lives. I’m committed to interacting with people in the midst of their everyday life because I don’t believe art should be separate from life. And I believe art can be a catalyst for change.

To view Janet Echelman’s complete portfolio of images from these projects and more, visit www.echelman.com/portfolio

_______________________________

Marci Rae McDade is the editor of Surface Design Journal and former editor of FiberArts magazine. She received an MFA in Fiber and Material Studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a BA in film and video production from Columbia College Chicago. She is also a mentor and instructor with the MFA Applied Craft and Design program (cosponsored by Oregon College of Art & Craft and Pacific Northwest College of Art) in her hometown of Portland, Oregon. You can find her on Facebook.

Marci Rae McDade is the editor of Surface Design Journal and former editor of FiberArts magazine. She received an MFA in Fiber and Material Studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a BA in film and video production from Columbia College Chicago. She is also a mentor and instructor with the MFA Applied Craft and Design program (cosponsored by Oregon College of Art & Craft and Pacific Northwest College of Art) in her hometown of Portland, Oregon. You can find her on Facebook.

Related Blog Articles

Conferences

“Domestic Spaces” — Out Now!

Conferences

Friday Fibers Roundup: Tight-Knit

Conferences

Friday Fibers Roundup: Artistic Approaches